Can We [E]racism today?

1) Please choose a scientist and write about what they were talkng about in the episodes we have watched or are watching. Please use your class network and get help from Mr.C to generate ideas on these very important topics. The last time we did this we looked at Havard Professor Hammond and her ideas on Race. Please write an 11 sentence paragraph if possible or a summary [Write path interactions list is an option]. As a reminder, you have had the handouts since the begining of the year. The quotes/questions are input and your opinion or writing will be the output. Notes or your discussions should be on the input side. 2) Then work on the comprehensions questions and choose a discussion question. 3) Please make a timeline too [For the timeline it does not if the matter input or output, but please annotate the timeline]. Lastly, as always ask for help when you are not understanding and follow the social contract with kindness.

PILAR OSSORIO, Legal Scholar / Microbiologist: We have a notion of race as being divisions among people that are deep, that are essential that are somehow biological or even genetic, and that are unchanging - that these are clear cut distinct categories of people. OSSORIO: All of our genetics now is telling us that that's not the case. We can't find any genetic markers that are in everybody of a particular race and in nobody of some other race. We can't find any genetic markers that define race.

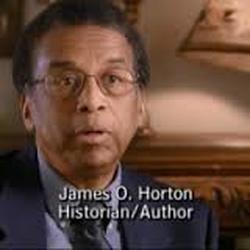

JAMES HORTON, HISTORIAN: And the way you do that is to say "Yeah, but you know, there is something different about these people. This, this whole business of inalienable rights, ah, that's fine, but it only applies to certain people."

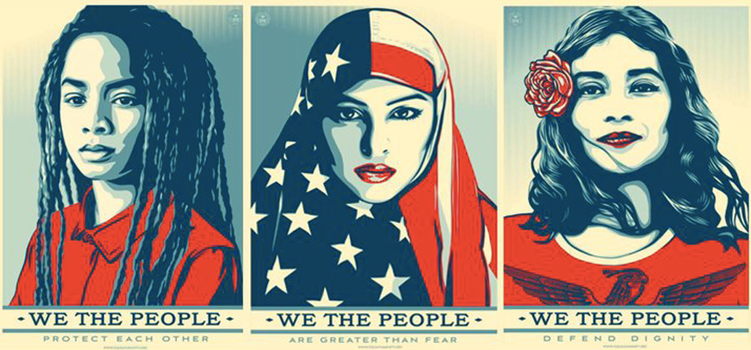

NGAI: Most white Americans really believed the West was for them, and for them alone. This was part of a whole philosophy of Manifest Destiny of what impelled westward expansion, ah, throughout the middle part of the 19th century. It was this idea that the West belong to white Americans.

RICHARD LEWONTIN, Evolutionary Geneticist: And the beauty of the race business is that you can identify people by just looking at them. You don't even have to look at their genes because one manifestation of their genes is there - namely skin color or eye shape or hair shape - and then that's the key to everything.

ALAN GOODMAN, Biological Anthropologist: To understand why the idea of race is a biological myth requires a major paradigm shift, an absolute paradigm shift, a shift in perspective. And for me, it's like seeing, you know, what it must have been like to understand that the world isn't flat. And perhaps I can invite you to a mountain top and you can look out the window and at the horizon and see, "oh what I thought was flat I can see a curve in now," that the world is much more complicated. In fact, that race is not based on biology but race is rather an idea that we ascribe to biology.

HORSMAN: Jefferson seems to have thought about it as a Virginia plantation owner who has been brought up amongst slaves, and who at his heart of heart, I would suppose, finds it difficult to conceive of those slaves are fully his equal.

Comprehension Questions

- > What are some ways that race has been used to rationalize inequality? How has race been used to shift attention (and responsibility) away from oppressors and toward the targets of oppression?

- > What is the connection of American slavery to prejudices against African-descended peoples? Why does race persist after abolition?

- > Why was it not slavery but freedom and the notion that “all men are created equal” that created a moral contradiction in colonial America, and how did race help resolve that contradiction?

- > Contrast Thomas Jefferson’s policy to assimilate American Indians in the 1780s with Andrew Jackson’s policy of removing Cherokees to west of the Mississippi in the 1830s. What is common to both policies? What differentiates them?

- > What did the publications of scientists Louis Agassiz, Samuel Morton, and Josiah Nott argue, and what was their impact on U.S. legal and social policy?

- > What role did beliefs about race play in the American colonization of Mexican territory, Cuba, the Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico?

- What is the significance of the episode’s title, “The Story We Tell”? What function has that story played in the U.S.? What are the stories about race that you tell? What are the stories you have heard? Did the film change the way you think about those stories? If so, how?

- Organizers of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair put on display people whom they defined as “other.” Although few would do this today, many still see others as distinctly different from themselves. In your community, who is seen as "different"? What characterizes those who are defined as different?

- In the film, historian James Horton points out that colonial white Americans invented the story that "there's something different about 'those' people" in order to rationalize believing in the contradictory ideas of equality and slavery at the same time. Likewise, historian Reginald Horsman shows how the explanation continued to be used to resolve other dilemmas: “This successful republic is not destroying Indians just for the love of it, they’re not enslaving Blacks because they are selfish, they’re not overrunning Mexican lands because they are avaricious. This is part of some great inevitability... of the way races are constituted.” What stories of difference are used to mask or cover up oppression today? Why do we need to tell ourselves these kinds of stories?

Who We AreLorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

|

Our HistoryLorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

|