Evangelical preacher George Whitefield embodied “this perennial radical Protestant idea of immediate connection between God and the individual soul,” as religion professor Stephen Marini puts it. Historian Harry Stout calls White eld “the divine dramatist,” and Daniel Dreisbach, a law and religion scholar, says White eld brought Americans together “by a common message of revival.” Essential question for notes: How would you describe Whitefield’s message of rebirth?

citation:

http://www.pbs.org/godinamerica/view/

NARRATOR: One man offered an answer. Reverend George Whitefield believed he could unite people with a simple message that everyone could share. For Whitefield, the surest path for a people seeking a new identity lay in being born again.

STEPHEN MARINI: Whitefield has experienced something he wants to call spiritual rebirth, which he defines as the transformation of the soul by the Holy Spirit of God. Boom, we're back to this perennial radical Protestant idea of immediate connection between God and the individual human soul. And he says, "That's it. It really happens. It happened to me.''

NARRATOR: Rebirth, he believed, could happen to anyone, anywhere. It had happened to him years earlier, as a student at Oxford. Preaching in England, he'd achieved huge popularity but run afoul of his Anglican superiors for his unconventional message.

Now he'd come to America. And as he traveled the country, preaching wherever he stopped, he found people eager for his message of salvation.

STEPHEN PROTHERO, Professor of Religion, Boston University: Even contemporary Christians now, even many evangelicals, they just don't believe in sin anymore. But in this period in American history, people believed in sin. And what they believed is that we were born sinful. We're not born good. Like, everything's not OK. We're born with things haywire. And unless something unhaywires us, turns us around, we're going to go to hell. And because the sin is so deep and so powerful and so strong, it requires, like, a powerful, you know, "Voom'' to turn it around, and that is the moment of rebirth.

So he decides he's not going to read these boring sermons like these other ministers are doing. They stand up in the churches and read these boring sermons that people are required to come to sit and listen to, hour after hour after hour, and not just on Sundays, either. And he's going to stand up and he's going to tell stories and he's going to speak from his heart. This is the key thing. He's going to speak from his heart.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: Methinks I see the good old man walking with his dear son in his hand-

HARRY S. STOUT: He's creating a scene. He's creating a dramatic scene. And the capacity, the faculty that he wants to draw on more than anything else is not understanding but imagination.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: -and now and then, looking upon him, loving him, and then turning aside to weep.

HARRY S. STOUT, Historian, Yale University: It catches the audience by surprise. They're caught up in the story and the description of Abraham and Isaac walking up the mountain, tears streaming down Abraham's face. And they're kind of locked into this message. It's one they've heard before, but he had a voice that could make people melt.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: I see the tears trickle down the Patriarch Abraham's cheek. And out of the heart and out of the abundance of the heart, the abundance of the heart, he cries, "Adieu, adieu, my son. God gave thee to me, and God calls thee away.''

HARRY S. STOUT: And then there's this abrupt turn, dramatic turn.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: I see you affected. I see your hearts affected. I see your eyes weep. And I would willingly hope that you are ready to say it is the love of God in giving Jesus Christ to die for our sins.

HARRY S. STOUT: He bursts onto the scene and he generates, in his own unique way, religion in a new key, a new way of understanding and engaging religion that was unprecedented. It's the sincerity of a missionary combined with the thrill of a performer.

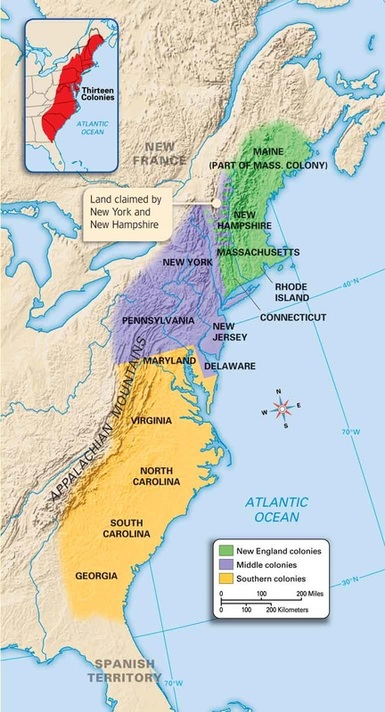

NARRATOR: As George Whitefield traveled through colonial America, he encountered dozens of different religious sects, but he quickly discovered that how they were treated varied enormously. The Puritans had renamed themselves the Congregational Church and were the official established religion in Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Hampshire. Funded by local taxes, they governed hand in hand with the civil authorities.

Other dissenting denominations were barely tolerated. Those groups - Baptists, Quakers, Lutherans, Catholics and Presbyterians - could find a home in other colonies. Rhode Island, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware had no official established church and tolerated many different religions.

But further south, a single official church had kept its iron grip. Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia were all Anglican colonies. Dissenting faiths were treated with suspicion.

In March 1740, Whitefield arrived in Charleston, the seat of South Carolina's powerful Anglican establishment.

STEPHEN MARINI: They think of themselves as the true religion that ought to have the state as its partner, and the dissenters either shouldn't be here or "We have to keep them under control.''

STEPHEN PROTHERO: The whole idea that we have now of religious pluralism, religious diversity is a good thing- that was just- it wasn't something hardly anyone thought of back then. The idea was that it was a threat to the unity of the state.

NARRATOR: As an Anglican minister himself, Whitefield was welcomed into the pulpits of Anglican Charleston. But his message of rebirth was not part of their tradition and shocked his fellow ministers.

STEPHEN MARINI: They say, "This is disorderly. There's not an article about you must be born again. You're saying it's necessary to be a true Christian. We actually don't believe that. We think if you conform and lead a morally good life, you're in.'' He says, "Oh, no, that's not right.'' And they say, "OK, you're not welcome here.'' He says, "Fine, I'll go out and preach in the fields. We'll send some fliers around and people will come.'' And they did.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: The Son of man comes to save all that are lost, all of every nation and language that feel, bewail, and are truly desirous to be delivered of their lost state.

NARRATOR: His Anglican superiors were appalled. They'd banned him from their pulpits, but he continued to preach.

STEPHEN MARINI: The Baptists and Presbyterians invite him over to preach, and he does. It's a scandal. The place is packed.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: He will in no wise cast out, for he's the same today as he was yesterday. He comes to sinners now, as well as formerly. And I hope-

NARRATOR: For Whitefield to preach in front of dissenting faiths was a direct challenge to Anglican authority.

FRANK LAMBERT, Historian, Purdue University: Whitefield ignored denominational lines. His message was, "There's the one thing needful. It's not needful that you are Presbyterian or Congregationalist or Baptist, or what have you. It's only needful that you have this life-changing Christ-inspired new birth experience.''

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: And I hope this day I will be sent out to bring you home, the lost sheep of the House of Israel. What say you? What say you? Come, friends. Would weeping, would crying prevail on you? I could wish my head were made of water and my eyes a fountain of tears that I might weep out every argument and melt you into love.

FRANK LAMBERT: There were plenty of people who said, "This is a sham. You're bringing disorder. Where's the verification?'' I mean, anybody can say, "I've had this experience, God has taken over me.'' In a sense, it was Anne Hutchinson's experience on a big scale. Now everybody is having this experience directly from God.

NARRATOR: Like Anne Hutchinson, Whitefield had fallen afoul of a religious authority that distrusted any message that gave an individual power over their religious experience.

HARRY S. STOUT: They were still part of a view of the world as a world divided between superiors and inferiors, and you had to know your place. And if you didn't know your place, order would break down and all chaos would ensue. Whitefield smelled the dissolution of the old aristocratic order. He saw that what had been was not what was going to be.

NARRATOR: In 1740, Whitefield journeyed 5,000 miles through America, preaching more than 350 times in 75 towns and cities. Twenty thousand came to hear him on Boston Common, twelve thousand in Philadelphia, eight thousand in New York City. In 15 months, as much as a quarter of the country heard his message.

HARRY S. STOUT: People couldn't talk about anything other than Whitefield. He becomes secular news, as well as sacred. The only name that Americans would recognize more than George Whitefield would have been King George III.

[www.pbs.org: Watch the series online]

DANIEL DREISBACH, Legal Scholar, American University: People that in a previous age would never sit down together in a religious setting, would not break bread with one another, and yet they're being brought together by a common message of revival.

STEPHEN PROTHERO: There's this wrestling match between you and God. And are you going to keep fighting God? Are you going to collapse into the arms of God? Are you going to, you know, feel the conviction of sin that's upon us? Are you going to pretend it's not there? Are you going to turn to Jesus and have him save you?

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: God had shown me what true religion was. It was a ray of Divine light that instantaneously darted in upon my soul.

YOUNG GIRL: Being at a meeting, I found my heart in some measure drawn forth to God. Sermon being over, my soul was filled with ravishing transport. My desires increased and my heart still reaching forth after God, at last I fainted.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: To be in him not only by outward profession, but by an inward change and purity of heart-

MAN: To talk so powerfully and wonderfully of the thing of God in Christ-

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: To be in him, so as to be mystically united to him by a true and lively faith, and thereby to receive spiritual virtue from him-

SARA: When the Reverend Mr. Whitefield came here and I attended his preaching-

MARILYN: -the best way. He speaks from a heart all aglow with love and pours out a torrent of eloquence which is-

MAN: -and are full of the love of God and Christ-

YOUNG GIRL: And looking forward, I see a place I thought was heaven.

MARILYN: New purposes and a new light from the day on which they heard-

SARA: My darkness vanished. My distress fled-

MAN: -were it not by the spirit and the power of the Almighty.

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: -in such a manner as the apostle, speaking of himself-

YOUNG GIRL: -and coming near, I see the gate standing open.

HARRY S. STOUT: And the next thing that happens is the realization, "We are the people. No one can silence this. No one can put this down. There is no standing army in the New World. There is no big police force. We are the law.''

NARRATOR: But the people were not the law, and the established church was. In Massachusetts, the Congregational minister Charles Chauncy began to publicly challenge Whitefield's populist appeal.

Rev. CHARLES CHAUNCY: Reverend Sir, the affection of popularity is the ruination of the soul and the destruction of understanding. But how wide am I from the mark to talk of conscience or scruple to one who is unsteady and variable as a weather-cock, and is yet enthusiast enough to boast of his frequent intercourse with the Almighty.

NARRATOR: Chauncy was an influential Boston minister who believed the new spiritual enthusiasm was leading congregations away from reason, away from the established church, towards social chaos.

FRANK LAMBERT: Chauncy said, "This isn't God's work. God's not a God of disorder. This is the work of a slick promoter.''

Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD: Reverend Chauncy represents things in the most ridiculous dress. He takes upon to condemn all the converts to a man, though he could not be acquainted with a hundredth part of them.

NARRATOR: But Whitefield was no longer that well acquainted with his flock, either. New, extreme ideas were finding a voice, and an following. Preachers like James Davenport went further than Whitefield, urging congregations to purify their faith and reject modern religion. He ordered his followers to burn the books of Charles Chauncy and other contemporary ministers.

STEPHEN PROTHERO: For Chauncy, reason is supposed to be important in religion and religion is supposed to be reasonable, which has to do with order. You know, what's going to happen to this society if it's turned so topsy-turvy?

NARRATOR: If Davenport's extremism could be dismissed by the establishment, it was more difficult to ignore the respected voices that now led the growing spiritual movement. Prominent thinkers such as Jonathan Edwards preached on the necessity of rebirth for everyone. And Gilbert Tennent focused his attention on ministers who had not been reborn.

FRANK LAMBERT: People begin to go back to their former congregations and challenge their ministers. "Have you had a new birth experience?'' And if the answer was no, or if the minister could not satisfy them that he had, one of two things often happened. One, he was fired, or two, people would leave and form their own congregation.

NARRATOR: Chauncy's fears were being realized. Established religions were fragmenting. Those fired by the message of rebirth were separating and offering people an alternative.

FRANK LAMBERT: So here is the day of services. There's the regular service. Now there's an alternative. You've got a choice.

STEPHEN MARINI, Historian of Religion, Wellesley College: If I'm being presented with multiple options, surely I must have the right to choose among them. It's not self-evident which one of these is true. And if God's spirit speaks to me through one of them, the state has no standing in telling me I shouldn't or I couldn't. The spirit is the absolute empowerment of my individuality. So my individual choice is not just an option, it is a divinely mandated course of action.

NARRATOR: People began to insist that it was their right to worship as they wanted in a church of their choice.

STEPHEN PROTHERO: So people start to have a sense of ownership over their own experience. It isn't so much they're reading some book and coming up with "Oh, liberty!'' It's more that they have the experience of liberty. They have experienced liberty. And this is the language Christians talk about, Christian freedom. They've have had the experience of freedom, of being freed from sin.

NARRATOR: Men such as the Baptist preacher Isaac Backus and the Congregational minister Jonathan Mayhew led calls for an end to established religion. Their voices joined the chorus for political liberty that was sweeping through the colonies.

The arguments over taxation and representation that had gathered momentum through the 1760s now found common cause with the cry for religious liberty. The revolutionary fervor had acquired a new moral force.

STEPHEN MARINI: In the act of defending their rights and their good service to the empire, they characterized themselves as innocent and virtuous.

STEPHEN PROTHERO: And in that spirit of things, the revolution becomes- if not inevitable, it becomes perfectly logical.

STEPHEN MARINI: And now- now the God of nations will surely look on our cause and see that it is just.'' And the sermons, dozens of them, begin articulating just this scenario.

MINISTER: King George III, adieu! No more shall we cry to you for protection! No more shall we bleed in defense of your person, your breech of convenant. The God of glory is on our side and will fight for us.

STEPHEN PROTHERO: And so as the farmer is picking up the rifle and putting down the plow and marching off, yes, he's thinking about, "I want rights.'' You know, "I want to be able to run my own society.'' But he's also thinking, "This is righteous. This is a righteous cause. And God is with us in this cause.''

MINISTER: We have reason to conclude that the cause of this American continent against the measures of a cruel, bloody and vindictive ministry is the cause of God.

STEPHEN PROTHERO, Professor of Religion, Boston University: I think America is a story. And Americans, as they move - as they first come here, as they move west, as they move out into the world - they're telling a story. And the story they're telling is a Biblical story. I think it's the Exodus story. They're telling a story about the movement of a people out of slavery into freedom, out of the old world into the new, out of the place of the Pharaoh, or George III, into this place of freedom.

And this started to become a new world instead of just the old world in a new place. And so much of what drives the story of America is figuring out what that new thing should be.

What should that new thing be?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed